I’m thrilled to welcome Linda Austin for this month’s guest blog.

As with all my guests so far this year, I first met Linda through the web of social media. I was immediately smitten by her story of growing up as a Japanese-American surrounded by midwest whiteness.

Since grade school, I’ve been eager to befriend the newly arrived Cuban girl, or the refugee from somewhere in South America. We had an exchange student from Spain when my sons were teen-agers, and for a number of years, I played host to young adults in Penn’s ESL program.

I easily romanticized the idea of living in a culture different from the one I was born to.

Linda’s story takes the romance out of that notion, while still making me smile at many of her images. That’s a powerful combination.

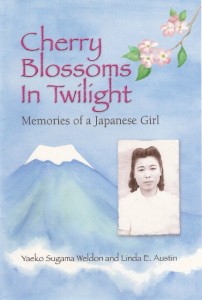

Linda Austin has published two books: her mother’s memoir, Cherry Blossoms in Twilight, and a short book of Japanese-style poems about caregiving, Poems That Come to Mind.

Linda is a board member of the St. Louis Publishers Association and of two Japanese-American organizations. She encourages life writing and provides self-publishing information on her website http://moonbridgebooks.com. And she is currently putting together a Korean War memoir.

Welcome, Linda. Take it away …

“What are you?”

How do you answer a question like that?

“Um, a person?”

Then the response was, “No, really.”

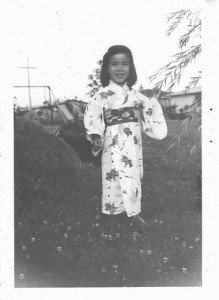

I grew up in the middle of a cornfield off the edge of a blue-collar town in the Midwest, went to school in a little farming community nearby. My sister and I, nut brown like ripe acorns from playing in the summer sun, tried to blend into the whiteness at school, and for the most part we did. Everyone knew us and we became like everybody.

Now I know we were lucky. We were half Japanese, and this was the 1960s and 1970s. In those days, half-Japanese growing up in other places in the U.S. had rocks thrown at them along with ugly names. Adults called small children ugly names and told them to get away from their kids.

Neighbors in our little isolated subdivision liked our interesting Japanese mom, though. Some were second-generation immigrants—Italian, German, Polish—and there was an English war bride. Maybe that made the difference.

I grew up American, speaking only English, but there were silk kimono and fancy obi sashes packed away in trunks smelling of mothballs, and sometimes we had fried wontons or tempura or vegetable sushi rolls for dinner. We ate rice—only Japanese rice—with everything, even Spaghetti-Os.

My mom told us stories of hunting for tadpoles in rice paddies or made our eyes grow big at weird Old Fox tales.

My dad took us to Japantown in Chicago every few months where my mom would stock up on food supplies from Star Market. That place was a cramped museum of unidentifiable food in packages we couldn’t read, rows of dead fish staring at nothing, barely-moving live crabs spilling out of low troughs of crushed ice. My sister and I cried for McDonalds while our parents frowned and ate sushi at their favorite restaurant.

It wasn’t until I went off to college that the questioning started. Suddenly I was not the only brown-skinned person around. Black kids thought I was one of them, so did the Hispanic kids. The Chinese kids seemed to know better. The white kids asked the questions.

“What are you?”

“Where are you from?”

Here, or I was born in Chicago was not the right answer.

I married, and my husband moved us around the country a bit. Somehow there was always a sushi restaurant near us, even in the days when those were a rarity. But, I didn’t really know any other Japanese people until many years later when we moved to St. Louis.

I had ghostwritten my mom’s stories into a memoir of growing up in Japan around WWII and put it up for sale on Amazon.com because there was no other book with that story. I became an advocate for life writing. The local newspaper wrote about my mom and me, and a Japanese-American women’s group found me and asked me to speak to them about the book.

I found “my people.” This half of my heritage is calling me loudly now. I have leadership positions in the small Japanese community and the big annual Japanese festival.

This spring I signed up for lessons at the local Japanese language school (I have only cried a little bit). Someday I want to go to Japan and meet my cousin and be able to communicate with her in simple words.

Sadly, my mother rarely went back to Japan to visit. She thought her family had disowned her when she married an American and left for the U.S., but my dad took her back ten years later and after some apologies all was well. My mom then returned by herself for visits only about every fifteen years because of the expense.

When she died a year and a half ago, my pain was also from the thought that I had lost my connection to the Japanese heritage I have grown to love. Then I realized it is still inside me as I fix bento school lunches for my picky-eater teen or light incense for my mother.

My quarter-Japanese children are very American, though, and mostly isolated from others of Japanese heritage. Once I am gone they will likely only know their Japanese side from a thin little book—Cherry Blossoms in Twilight: Memories of a Japanese Girl. That and the silk kimono they inherit.

###

In addition to her website (above), you can find Linda on

Twitter @moonbridgebooks

Facebook Moonbridge Life Writing & Memoir and her

Amazon author page at Linda E. Austin Amazon profile

###

Thank you, Linda.

I love the image of eating rice, “with everything, even Spaghetti-Os.” In fact, your post is filled with lush, poetic images. No wonder I think of you first as a poet.

I grew up in what we would now call a “heavily integrated neighborhood” in East Orange, New Jersey, and learned very early that skin color is rarely a sign of anything other than skin color — something akin to hair color.

As I look back, I sometimes think the larger cultural differences at the time were between my WASPishness and the “other white group,” the Italian-Catholics that also populated my high school. But then, those differences weren’t only not important, they were invisible to me.

The differences that stood out to me, the ones that made me feel like an outsider, were my stuttering and the size of my family: two. I had neither father nor siblings. And, worse, I knew no one else in either category. A most unusual arrangement in the 1960s.

I think when we are in high school, fitting in takes on much greater importance than it does as we grow older. Perhaps that’s the “wiser” part of the age-related trade-off. As we grow older, being different becomes less frightening; perhaps even welcoming?

How about you? What were the differences surrounding you as you grew up? How easy is it for you, today, to stand apart from the crowd, to be different? Can you celebrate your differences, yet?

Kathleen Pooler

Dear Janet and Linda, this is a fascinating discussion. I thoroughly enjoyed both of your books, Linda as well as your deep connection with your Japanese ethnicity which will live on because of your writing. I feel I have meet your mother. Preserving ethnic tradition is a gift we give future generations. I grew up in a “vanilla” world–an all- white community and school. The only two “cultural” aspects I dealt with were identifying with my Italian heritage and being Catholic. It wasn’t until I went out into the world that I learned to appreciate other cultures. Thank you both for sharing!

Janet Givens

Good morning, Kathy. Always good to find you here. Thanks so much for starting off our conversation this morning. That ability to “appreciate other cultures,” as you say, is such an important one in our world today and I’ve seen you appreciate them well. I’m glad to know you. (Hello to Susan today, too)

Marian Beaman

Lovely story, book covers, and author. Thank you, Janet, for introducing us to the most engaging people. As for encounters, I discuss a similar topic on my own blog today, as it happens.

My differences? Growing up Mennonite, my prayer veiling and conservative dress set me apart from most in my class though plain people were not an oddity in Lancaster County, PA at the time. I have learned that what makes one different often makes one special, and in a good way. It’s what we write about.

You have certainly found your niche, Linda.

Janet Givens

Marian, I scooted right over to your blog and fell in love with your images, like this one: “non-verbal cues and nuances of personality and facial expression are often masked by the limitations of tiny pixels on posts.” Pixels on posts! Indeed.

Your comment reminded me of an adage from long ago, something about “We are all the same, in our own unique way.” Or was it “We are all unique, just like everybody else.” Something like that. I’m off to your blog to leave a comment about meeting up with Kathy Pooler on my last trip to Ohio. Cheers.

Marian Beaman

Thank you, Kathy!

Linda Austin

Thank you, Kathy and Marian. Yes, there are all sorts of ways to be and feel different. I’m glad things have changed in the US and we have more cultures and other differences that are now embraced, and yes, as we get older we usually come to feel more comfortable with ourselves. I love learning about everyone’s differences! Marian, I am following you on Twitter, now. Thank you, Janet, for hosting me. I look forward to reading your book when it comes out.

Janet Givens

I’m reminded of a quote from Gregory Bateson, best known as Margaret Mead’s husband, but a great anthropologist in his own right. He said, “the trick is to know which differences make a difference.”

Kelly Boyer Sagert

What a great blog post!

I was blessed to grow up in — and still live in — the “International City.” This was a nickname given to Lorain, Ohio (30 miles west of Cleveland) because of all the people from around the globe who immigrated to Lorain for manufacturing jobs: boat building, steel production, auto manufacturing and more.

Linda Austin

Thanks for stopping by and commenting, Kelly. How nice to grow up with a more worldly perspective. As a child I loved visiting Chicago every few months – thank goodness for that!

Janet Givens

Linda,

Your comment about Chicago reminded me how I had New York City in my backyard while I was growing up. Not only did my h.s. friends and I go in there on occasion, but earlier, probably grade school and younger, my grandmother would often take me in for a day — usually culminating in something at Madison Square Garden (horse show, dog show, circus, ice capades, Billy Graham rally, etc.) For a day, I had New York at my fingertips and I loved it, all of it. Still today, when I arrive in NYC, the first thing I do is giggle.

Janet Givens

Hi Kelly, I love hearing that Lorain found a way to show its appreciation for its own diversity. I wonder if the different immigrant groups gathered in enclaves for a few generations or if they mingled in housing and therefore nearby schools from the start. And I’m particularly interested to know if you aligned with one of the groups when you were a kid? Or had they all assimilated in one big stew by then?

Kelly Boyer Sagert

Different groups settled in different parts of the city, often building churches and social halls specifically for their culture.

I never aligned with any one group, but we still enjoy food from different cultures/ethnic groups at festivals and so forth. You’ll have to come to the International Festival one year – it’s late in June and we get about 100,000 people that weekend.

Janet Givens

Thanks Kelly. Sounds like a plan: June of 2016