One of the unsung gifts of cultural difference is that we begin to see our own culture anew.

So it was with me in the Kazakhstani classroom. In case you’re just joining us and haven’t read my book (yet), I was an English teacher — a native speaker — in a pedagogical college on the Kazakh steppe from 2004 to 2006. My students would graduate with a diploma that would enable them to get jobs as English teachers in the primary grades. By presidential edict, English was to be taught throughout Kazakhstan beginning in the second grade, so all my students would find good jobs. The problem was, not all my students would make good teachers.

One of the oft ignored challenges of culture shock, is that we begin to see the world in terms of black and white: good and bad, right and wrong. We miss those murky, muddled grays that are so much a part of life. As the stress builds, we begin to want to simplify our life. One way to do this is to seek simple answers; that’s fine, if the question is also simple. It’s a real problem, though, if the question is actually complex.

In preparation for this blog post, as I read this deleted scene, this maxim came clearly into focus for me.

Here is the scene, interspersed with some 2015 photos.

American teachers, the ones teaching at American universities, colleges, and even some high schools, are spoiled.

This is not to say they don’t work hard; I know first hand, living with a college professor, that they do. But still, American teachers can’t possibly work as hard as my teachers here in Kazakhstan.

American teachers have students who are, generally, prepared. If not prepared, they’re at least capable of doing the work. And if they’re truly not capable of doing the work, the teachers have some recourse: they can fail them, give them an Incomplete, or at least a Saturday detention — something. There’s always something they can do; that’s the American way.

Yes. American teachers don’t know what frustration and impotence really are. In comparison to my teachers, they’re spoiled.

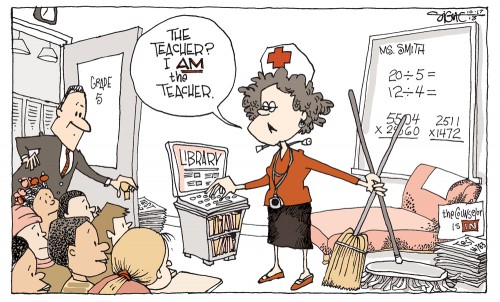

In Kazakhstan, there are no teacher aides, no teaching assistants, no parent volunteers, and no substitute teachers. If a colleague is absent, her classes aren’t cancelled. Her colleagues cover her classes in addition to their regular load. And they don’t get paid extra.

My teacher colleagues here in Kazakhstan have classes of 26, smaller than many American classrooms, but many of the students are there only because their mothers think a diploma as an English teacher is good to have. The classrooms in Kazakhstan hold anyone who’s finished ninth grade.

All of the classes have at least two students who never come to class.

All of the classes have at least three students who come to class but want to be somewhere else.

All of the classrooms have at least five students who in America would still be in grammar school, repeating the eighth grade.

All of the classes have at least five students who sit there, wanting to be good students but have no idea how and rarely open their mouths.

And all of the classes have at least five students who attend class regularly, want to be there, know what’s going on, are eager and hungry for education, and make all the frustrations seem insignificant. I think of Gulsana, Aida, Yestai, Gulya, Dinara, and Zamira in last year’s English 49, and of Binur and Donna in last year’s English 31, and I can’t help but wonder just how much more they would have gotten out of their class time if I hadn’t had to deal with the other students.

Yes, the teachers here have challenges most American teachers never dream of. I wonder if Kazakhstani teachers ever imagine themselves teaching from a text book that uses correct English grammar? Might they envision a class where all the students have their own text? Where they can walk into a classroom and find chalk just sitting at the blackboard; and have a blackboard they can actually write on?

This year I have the promise of some great students. This year’s English 49, Russian group, still has Anastasia, Gulsim, Ainura, Zhanel, Victoria, and Lisa who excel. And this year’s English 40 is a good one with Aigerim, Azimat, Gulsaira, and Meka among others. English 49 is a weaker group this year than last, but it has a few sparkles. And of course I’ve got Raikhan, Nurkien — who wants to be called Nick — Sandy, Aigul, and Aktolkyn in this year’s English 39 — a third-year group. And I’ll have each of these groups for three different classes; how great is that!

How about you? As you read about the challenges of teaching in a Kazakhstani classroom, what comes to mind of your own American or western school experience? How do you compare the challenges that American teachers face?

Marian Beaman

Spot on, Janet. My son Joel can relate to graphic # 2 – research has shown that recess and the arts help learning in other areas, yet the powers that be persist in their wonky thinking. It’s maddening!

Your students look happy and engaged in spite of a paucity of materials – and it wasn’t the teacher’s fault. That’s for sure! I’d give my experience teaching college a 9/10 rating. I miss it except for the essay reading.

Janet Givens

Happy and engaged; yes, they were, Marian. That’s a good summary of that final year. And I so relate to the “except for the essay reading.” That was the final straw in Woody’s decision to retire early; he was teaching a writing intensive class and too many students weren’t even at a high school level. Reading a deluge of good essays is a lot of work; reading a deluge of bad ones is torture. (Did you catch my typo in the first few lines above? All gone now).

L. E. Carmichael

I can’t speak so much for teachers, but something that amazes me about the North American university students I encounter is how many will pay tuition and then not go to class. It’s incredible to me that many students don’t seem to recognize how lucky they are to have the chance to go to university in the first place, and how many don’t take full advantage of the opportunity they are paying for (despite complaining about the cost of tuition). North Americans do seem to have some very odd attitudes towards education!

Janet Givens

Hi Lindsey, My only experience teaching at the university level was two semesters as a Ph.D. student. I taught a required 8:15 a.m class in American Government and it was not an inherently rewarding experience. I had no idea so many students were so unmotivated. I remember one in particular who turned in an essay on the current presidential campaign (1992) and repeatedly spelled the current president as Busch! I took points off for that and she complained. My Kazakh students were a real gift in comparison.

Ian Mathie

That’s not confined to the US. We have similar attitudes here in UK, where not attending lectures is almost a sport with some students who then go on to protest when their marks are low.

One of the greatest joys for any teacher working in the emerging countries, and Kazakhstan must be one of these, is the genuine enthusiasm for being involved that almost every student displays. This is even more evident in Africa where the thirst for education will make children willingly walk ten miles a day just to attend school.

In the west we are too complacent; everything is too readily available, and privileges have become ‘rights’. Few understand how lucky they are.