My guest today is Ian Mathie. I first met Ian just a little over a year ago on Belinda Nichol’s blog, My Rite of Passage. I was struck immediately by this sentence of his:

“But there are stories about people and cultures that, if they are not recorded, might be lost to the rest of the world—people who deserve to be remembered, histories that should not be sacrificed in the name of progress.”

Now here was my kind of memoirist.

Here’s his bio:

Born in Scotland, Ian was taken to Africa when he was three and began his schooling in a mission school, with lessons in the morning and the African bush as his playground in the afternoon.

Growing up with Africa enabled him to absorb the culture from within, so on returning to Africa after secondary school and military service, to work as a rural development officer, he adapted very quickly to life alone in the bush.

Working primarily on water projects, he has worked in almost every African country, spending thirty years there before returning to Europe and retraining as an industrial psychologist. (He insists there’s a logic to that).

When a medical condition curtailed his travelling he settled down to write books and has so far produced six volumes of African Memoirs, one novel and one small book of poetry. He now lives in a small village in the UK with his wife and dog.

Ian has five memoirs from his many years living among the various cultures and nations of Africa: Bride Price, Man In a Mud Hut, Supper With the President, Dust of the Danakel, and Sorcerers and Orange Peel. I’ve started at the beginning, with Bride Price — action packed, yet with fully-fleshed out characters that I’ve come to know and enjoy — and hope to wind my way through the rest of them over the summer.

AND, he welcomes feedback from readers.

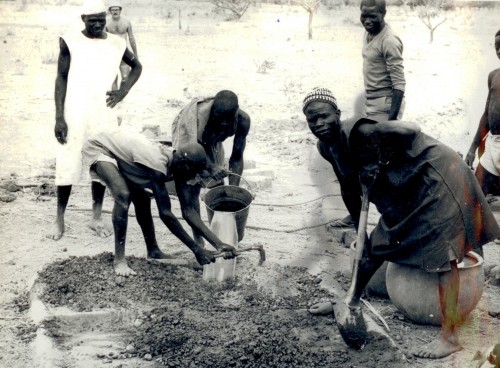

WELCOME, Ian. And thank you for the photos that intersperse your story.

****

The Richness of Cross Cultural Experience — Ten Lessons One Learns

Growing up in the African bush meant that when I returned after my education was completed and I’d done four years military service, I had no trouble settling to life in isolated villages as a rural development officer. Learning the local languages only took a few months, and before long I reached the point where I could discuss matters of cultural interest, beliefs and so on, as well as those issues concerned with the job.

As part of the government’s overseas aid programme, I was to oversee a number of existing projects, and initiate new ones according to a loosely written brief. It soon became apparent that the brief bore little relation to the actual needs to the recipients, and telling them what they needed was not a good approach.

An old man who had never been to school, who could neither read nor write, but who had command of six different languages, and several dialects of each, pointed out that I was equipped with two eyes, two ears and one mouth. It would serve me well, and everyone else, for that matter, if I used them in those proportions. Fortunately I had the sense to listen, and it was one of the most valuable lessons I ever learned.

Soon afterwards I met an old Belgian missionary, a Catholic priest who had come to West Africa over thirty-five years before, with the instruction to convert the heathen and bring them into the fold. On his arrival, Father Bernhardt found that the people in his new parish were destitute. Their farms were meagre and unproductive, and they were all hungry for food, not spiritual guidance. Their own shamans and spiritual men were clearly powerless to change this situation, so he decided that nourishing their bodies was necessary before he could counsel their spirits.

He started a farm school, and taught then to grow good food. He got help teaching the women about nutrition and hygiene; and as he worked with them he learned about their ways, beliefs, and culture. Every Sunday he went to the small church his predecessor had built, it was little more than a cabin, and said mass. In time, the two or three people still living there who had accepted instruction from the previous priest came to join him.

After two years the farm school was going well, and he feltit was time to begin his primary mission. He invited all who were willing to help to come and make bricks with him, as he intended to build a church. On every brick the name of the person who made it was inscribed. Since most could not write, he taught them, and before long the brick makers were writing their own names on their bricks. Soon their children wanted to join in, so he taught them as well. Long before the rains came, he started work on building his church.

During all the time they had been making bricks, Father Bernhardt talked to the workers about God and his teachings, relating what he said to their own beliefs and spirits. When the first part of the church was finished several dozen came to listen when he said mass the next Sunday morning. By the time I met him his regular congregation had grown to over three hundred and fifty.

I learned from many events and many people all over Africa, but these two stand out because they were early in my working years, and greatly influenced my thinking. My whole approach to the job was transformed and developed a consumer focus. It was evident that people generally knew what they needed, and certainly knew what they wanted. If I tried to foist something else on them it would be abandoned the moment my back was turned. So I exploited their wishes, and became a catalyst to help them achieve what they most needed. This, in the early days, invariably revolved around their water supply, which was often precarious.

I had access to all sorts of gadgets for finding water and for working out how deep below ground it was. But it seemed wiser to let their own diviners identify these places, and merely to confirm them with my instruments. Then, if the water was either deeper than predicted, or less plentiful, they couldn’t just abandon the well and say it was my fault there was no water. When they had chosen the site themselves, people always worked more willingly and more enthusiastically. They would keep digging until they found water. On one well in Togo this took us to a depth of 72 metres! But we found good water, and that well is still in use today, forty-two years later.

Tribal Africans do not separate spiritual life from the mundane physical daily grind. When people die, even though their bodies decay, they do not depart, but remain present as ancestors, who should be consulted whenever decisions are made. Shamans, sorcerers and witch doctors provide the interface between the physical and the spiritual worlds through which this can be done.

They also serve to speak with and propitiate all the other spirits and gods that inhabit the world and which influence the people’s daily lives. Their contribution is often essential for any project to succeed. Whilst there are undoubtedly some who are in it for their own benefit, they can exert an inordinate influence over people’s attitudes and willingness to contribute and participate. So offend them at your peril; sometimes literally, as the use of poisons, let alone magic spells, is far from uncommon.

As well as practical and working lessons, I discovered an extraordinary wealth of interest and wisdom in the varied cultures of people in the bush. They inhabited very different environments, from the searing heat of the desert; through broad, grazing savannahs; to rich cultivated parkland, growing grains, groundnuts and sugar cane; mountains, where two crops a year could be harvested as long as the monsoons didn’t fail; and deep tropical forests, whose people harvested the jungle’s bounty whilst living in a permanently soggy, dimly lit environment. There were exciting cultures, with tremendous diversity of beliefs, customs and traditions. Living alongside these and being allowed to participate, and even, on occasions, being initiated into their fold, was a rare privilege that offered a level of understanding not available to most outsiders, or to tourists.

These experiences, and many of the wonderful people I met, now fuel my writing. Since truth can so often be stranger than fiction, and Africa offers such variety of extraordinary truths, I have discovered that telling their stories in memoirs can make gripping reading, every bit as exciting as any novel. And it has the advantage that I don’t have to make anything up.

The old adage says you can only get out of life what you put into it, is most emphatically true. Being willing to meet others in an open, friendly and co-operative way is essential; and to understand that you can only achieve things through your own efforts.

Africa thrives on proverbs. The first I ever learned has lasted me a lifetime and proved itself time and time again. So I’ll offer it to you now: Kila ndege hurukwa kwa bawa lake – Every bird must fly on its own wings. Think about it, and then stretch out your own wings.

The lessons:

- Look and listen more than talk

- Exploit people’s desires

- Let people choose; then they won’t give up

- Put ideas in contexts people understand and value

- Learn the system and get involved

- Use the local talent (including the sorcerers!)

- Choose your timing carefully

- Always be open, friendly, and co-operative

- Let people fly on their own wings

- Always be positive and avoid “don’ts”

Thank you, Ian. There are so many avenues to persue in what you have written.

I love how you’ve summed up your experience with these ten lessons that we can all pay attention to. I particularly like “Exploit people’s desires.” And I love that you’ve used a word, exploit, which we ordinarily think of as perjorative, in a very positive way; to describe, quite aptly I think, just what it is you’re doing: making the most of their energy around what it is they already want. To do that you have to listen. That is just what the Peace Corps is about as well.

To do that, it seems to me, we have to let go of that “my way is the right way” mentality that pervades so much of any culture. And that’s not always easy to do.

How about you? How hard would it be, or has it been, to give up your way of doing things, to try on a different way of being in the world? Have you found it exhilarating or quite frightening? Both? Or something in the murky middle? Do tell us your story.

Ian has graciously offered an eBook copy of any of his books to one of our Commenters (Drawing on Sunday). And, he’ll offer a free paperback if you’ll go to England and pick it up.

possum

What an interesting post! Can’t wait until I can get a copy of his books. And really good advice!

Janet Givens

I’ve just started on his series, J, and thoroughly enjoyed Bride Price. There’s no ethnocentricity in his writing that I could find. Quite an amazing accomplishment. Thanks for stopping by.

Yvonne Hertzberger

“It soon became apparent that the brief bore little relation to the actual needs to the recipients, and telling them what they needed was not a good approach.” This is the sentence that has told you what you needed to be successful in you8r life;s work Bravo.

BTW, I loved “Sorcerers and Orange Peel”. It was a wonderful introduction to understanding Magic Realism,

Janet Givens

Hello Yvonne and welcome. So glad you stopped by for Ian’s post. You mentioned “Sorcerers and Orange Peel.” I’m aware of how enticing all of Ian’s titles are. Each one conjures up and image, and I’m hooked into reading to see how close my image is to his truth.

I hope you’ll come by again. I love your website, btw. Great color combo.

Jacob Singer

I enjoyed reading Ian’s books. They brought back many memories of Africa as it was and in some places, still is.

Today Ian and I keep in constant contact via email. He has become a good friend.

Janet Givens

Hi Jacob. So you’ve been in Africa too? Where were you, when, and … well, I’d love to hear a bit of your experience. Do tell us more. And thanks for stopping by. — Janet

Ian Mathie

Jacob is an African through and through, Janet. He too grew up with it and only recently moved to ‘foreign climes’ (i.e. the US.)He know Africa, watts and all, and has written two brilliant books about some of it which are well worth reading. They show another face completely, but then Africa has many faces.

Sharon Lippincott

Thank you Janet for featuring Ian in this delightful p post. I’ve read and written five star reviews of each of the five African memoirs, and this post had still more material and insight. I suspect Ian could fill several more volumes and turn to other equally fascinating eras.

Those ten lessons comprise a plan for life that I shall most surely pass along to my grandchildren who are currently flying the nest. Its true strength lies in the fact that it’s dogma free, applicable to any belief system. This is the best kind of street smarts. Thank you Ian for boiling it all down.

Janet Givens

Hi Sharon. I’m so glad you popped in. I find it hard to believe you have grandchildren old enough to fly the nest. You must have begun your family when you were nine!

I noticed your name among Ian’s reviewers when I posted my review of Bride Price last night. I felt the same way about it as you did: action-packed yet with a depth anathema to most action stories. He was indeed the hero of his own story, just as a memoir is meant to be. And, let me add that I loved your recent blog on friendship; I only wish I’d seen that Faulkner quote earlier. It would have made a great ending to my book. Have you heard the one “Friends are a reflection of the issues we’re working on.” That’s a personal favorite.

Do come back and visit us again, heh?

Sharon Lippincott

Janet, nice to recognize a kindred spirit in a “friend” I’ve been connected with for who knows how long. I love that quote about friends and issues. Thank you for that. Will be back.

Ian Mathie

Ii is interesting that you saw me as a hero, and that’s not what I wanted to portray. I was merely a bystander to the story. I wrote Bride Price to tell Abélé’s story, both as a memorial for her and the villagers we lived among, and to share some of the culture and their lifestyle, which is vanishing so fast. That area has now been devastated by two civil wars, and raped by loggers who cut down all the forest.

Sonia Marsh/Gutsy Living

I’m so glad you invited Ian to guest post Janet.

As you know, I’m considering the Peace Corps and after reading several stories about PCV and their experiences in Africa, the #1 mistake they say they made, is that they jumped too quickly into trying to change the locals, or teach them something when they weren’t ready. As I mentioned earlier, TRUST is a huge issue, and unfortunately I learned that lesson the hard way during my family’s year in Belize.

May I link to your post in an article about the Peace Corps I want to write? I also want to use Ian’s 10 lessons and give him credit. Thanks again to both of you, and I also enjoyed Ian’s first memoir, Bride Price.

Janet Givens

Hi Sonia and welcome back. I’d be honored to have you add my link to your article. Good luck with Peace Corps. I’ll be interested to read your article.

Rosanne Dingli

Even though I’m having serious connectivity problems this week I could not resist a visit here to the author of some of my favourite books. We are having a big cull in preparation for our down-sizing in a few years, but Ian’s set of African memoirs are coming with us. This was lovely, and a great taster for what this amazing writer provides. Thank you both.

Janet Givens

As someone who had to weed through my books before we went in Peace Corps, I think you’ve given grand praise indeed. Thanks for stopping in Rosanne. Glad you are here. — Janet

ian Mathie

Thank you Rosanne. It’s so rewarding to know my books are appreciated like that.

Janet Givens

Ian, this one is to you: 1. When I first arrived in Kazakhstan, I suffered enormous culture shock. I knew it, and didn’t let it deter me. Nevertheless, I did struggle in the beginning with all the “newness.” Did you ever have periods of exhaustion at the differing ways or did your African upbringing enable you to blend in as smoothly as you seemed to in Bride Price?

ian Mathie

No, I never suffered from culture shock in Africa, even though there is tremendous diversity in cultures. Even so, they all have some qualities in common, and I must have absorbed these during my childhood days. Approaching a new culture with an open mind helps as well and I was soon able to find my feet.

Having said that, I have seen others go through tremendous culture shock and this is a central theme to one of my books, Man in a Mud Hut My colleague, Desmond had a lot to cope with, but with a little help fro me, and a lot from our local witch-doctor and the villagers, he came through and learned to love Africa.

Janet Givens

Funny, I don’t think anyone could have approached her years in Kazakhstan with a more consciously open mind. YET, the immersion in a world that was so very different from what I knew (though it didn’t look all that different) and so constantly different really threw me. I had great intellectual understanding of culture shock, barriers to assimiliation, etc. before I went, yet the actual experience of it was overwhelming. At least for a few months, after teh honeymoon wore off. So, I’m more curious than ever to read a memoir of your growing up years in Africa. Any plans along that line?

Ian Mathie

Back to the question on culture shock: I note you say you had considerable intellectual understanding of the problem before you went, but the reality was worse. Maybe you’d been over primed and were subconsciously expecting it? Sometimes it is better to walk into something strange to you in a state of some ignorance and without expectations. A briefing is useful, and an open mind essential, but too much priming can taint the open mind. Discovery is one of the key elements in overcoming culture shock, and that comes easier when the field is not cluttered by expectations.

Janet Givens

Hey Ian, I’ll respond here to the “hero” comment above so people reading on their phones won’t have a long vertical stream of single words.

I’ve yet to meet a hero who hasn’t said they weren’t. (Wait; do Brits do the double negative thing? I’ll rephrase). I’ve yet to meet a hero who has said they were. Really, I think it must be part of the hero’s identity that he (or she) minimizes their role. So, sorry. Not taking your word for it here. You came through in the pinch, time after time. I felt quite sad, btw, when I read the epilogue. I’d know what happened in Zaire/DRC, but I kept hoping somehow Abele had followed you to the UK. Very sad.

Ian Mathie

Sadly that was not to be. Abélé saw her destiny very much among her own people. Having had parents who were sorcerers, she too was niseke, and so had a very special role to fulfill. Life isn’t always kind, although western minds so often wish it to be, but understanding what must be is part of African life. She and I both knew this, and it’s what you do with the life you have that counts. She’s not lost now, she’s become an ancestor, and that still counts.

Janet Givens

I loved your comment, “Discovery is one of the key elements in overcoming culture shock…” I would agree, and add that adequate sleep is equally essential. At least that’s what I found. 🙂

What struck me about Bride Price (I’m eager to get to Mud Hut now) was your complete faith in the culture you were immersed in. That is not easy to do. Indeed, I’d say most people cling to the culture they know like a lifeline. It’s HARD to let it go and accept a new way of being in the world. The fact that the culture(s) of Africa were not as foreign to you as they might be to other westerners makes, to me, an enormous difference in your ability to fit in and to be accepted.

So, I’m wondering about culture shock for you in the OTHER direction. How has living back in the West been for you? Life among the UK natives, so to speak? What sorts of adjustments did you have to make, if any?

Ian Mathie

Here I’m a fish out of water. It isn’t my own culture. I came from the north of Scotland, where, being tribal, the culture has more in common with Africa. In England I don’t understand how a lot of things work, am confused by the ever increasing demands of technology, and find the isolationist attitudes quite hard to get to grips with.

Retreating to Africa through books is one way out, and in the meantime I stumble along and often wonder why I bother. I find much of UK culture disappointing and off putting.

Janet Givens

Ian, we may be related. My father’s mother’s people came from Lanark, the ship’s registry says. In 1800s, I think, possibly mid-1700s. Getting to Scotland and doing some geneology, has been on my bucket list for awhile. I have very little information on them except that an ancestor in the 1600s was named Griselda. I love that. It’s gotten me interested in Scotish history, which is of course not taught here in the states. I’d never before heard of Culloden!

Toi Thomas

This is a wonderful article for so many reasons. Aside from offering insight into how do deal with other cultures and how to immerse yourself in one to get what you need out of it, I think this article is a wonderful guide for understanding people in general.

Janet Givens

Toi, hello and welcome. Thanks so much for stopping by. I hope you’ll feel free to share the link. And do come back. I took a look at your website and love the play on words, Toi Box. Very clever.

Ian Mathie

Toi’s writing is pretty good too. Unusual and challenging, it is full of imagination and looks at some of life’s relationships from and unexpected perspective.

Janet Givens

Ian, It’s been a full week, with lots of new people coming by to say Hello. Thank you so much for being with us and sharing your experiences. I’ve just downloaded your second memoir, The Mud Hut one and am looking forward to reading it.

As promised, I’ve held my magical little drawing and JanJan in Virginia (who goes by Possum here) is the lucky winner. I’m so glad, since she mentioned how eager she was to read Ian’s books.

So, Jan, write me privately with your preference in eBooks and your preference among the five memoirs Ian has written and he will get his publisher to send it to you.

Thanks again everyone. I hope you’ll drop by again next week.

Blogdom July, 2014 | The ToiBox of Words

[…] -From Janet Givens, The Richness of Cross Cultural Experience – Ten Lessons One Learns […]

In Memory of Ian Mathie – Janet Givens

[…] is that post, from July 16, 2014. (I’ve linked to it if you’d like to see the […]