Conflict, difference, disagreement, even misunderstanding can arise unexpectedly during the course of anyone’s day.

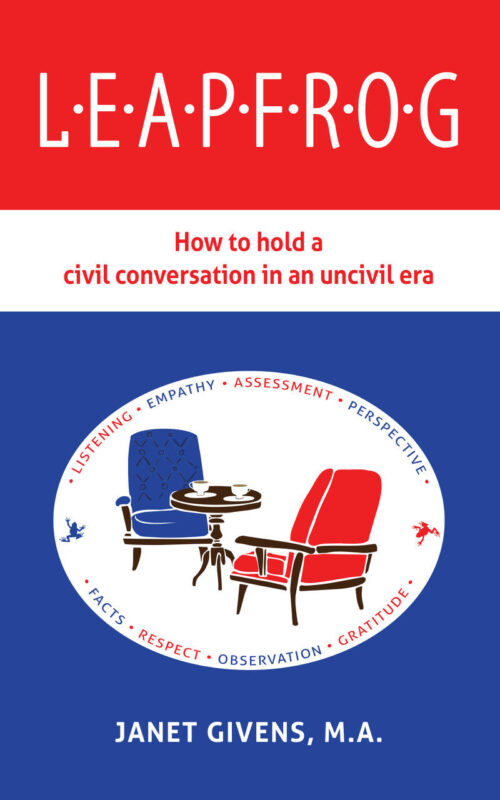

While remaining civil is not always easy, hate and fear are neither the natural nor necessary responses to difference. Nevertheless, we get triggered, sucked into an argument we didn’t see coming, propping one set of facts up against another with neither side listening, and eventually wondering what the hell just happened. We can come together again, though. Participating in a non-judgmental conversation on matters of importance gets us started. LEAPFROG presents the combined wisdom of many on how to be heard -- and how to hear -- without judgment. That's when the magic happens.

The eight concepts forming the acronym LEAPFROG are designed to

- help us both hear and be heard as we strive to

- understand the other’s point of view. It also supports us to

- stand firm in our own beliefs without imposing them on the other.

Are you part of a group that might adopt LEAPFROG for a few months? This book is designed to be used in a small group, with support as the reader practices the ideas presented. Taking a chapter at a time, whether weekly or monthly, has proven to be a useful model in better absorbing the principles presented.

As important as politics are these days, this book is not limited to political conversations. The ideas given here can be applied to any conversation you deem “difficult,” from marital disagreements and parent-teen clashes to neighborhood standoffs and workplace disputes. And so, perhaps a more inclusive subtitle would be, How to Hold a Difficult Conversation at a Difficult Time.

Here’s a brief taste of the new Introduction:

INTRODUCTION

Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change we seek. Barack Obama (1961- )

The aim of this little book is simple: to get us all talking again, civilly, with those with whom we disagree. Civil discourse, it’s been called, and it was once taken for granted.

Evolutionary biology is quite clear that we are hard-wired to treat differences with suspicion; our caveman ancestors weren’t singing Kumbaya around that campfire, to be sure. So, it is understandable that the idea of talking through conflict can feel so uncomfortable as to be off-putting. Engaging in civil discourse about topics on which we disagree may not come as easily as we’d like, but, after spending the last five years reading what so many others have to say on this topic, I’m convinced that we must bring it back, and that we can.

My premise is that learning to manage conflict is possible if we are willing. Think about that. While it may never be actually comfortable, we can learn to disagree without being disagreeable, and we can do it without abandoning our political and philosophical beliefs. This book explains how.

My memoir, At Home on the Kazakh Steppe, emphasized how exciting, enlivening, and enriching cultural differences could be. In that memoir and in the blog posts that followed, I wrote about how cultural differences (though also often exhausting) add spice to our lives as they help us learn about ourselves. I was particularly interested in those cultural differences, both at home and abroad, that “made me gasp” because they often taught me what I’d not noticed of my own culture. Eventually, I’d wind up smiling in understanding.

Following the US Presidential election in 2016, I found myself confronted with cultural differences I could not imagine ever smiling about. I gasped, metaphorically, for I’d grown up with ever present news stories of the corruption, deceit, and playboy antics of the man soon to be occupying the people’s White House. Juxtaposed against the elegance of the early ‘60s Camelot era that had helped form my political identity, I was afraid for my country and its future, angry over the absurdity of it all, and sad that I felt so impotent to do anything about it.

As incivility rose that year and into the next, my Facebook Friends list thinned a bit and I found myself wondering why we were all having such trouble being civil. More importantly, why did I not want to engage with any of “them?”

When I was growing up in the 1950s and ‘60s, the Emily Post books on etiquette taught that, in polite conversation, we must stay away from politics and religion, two topics that are central to how we see ourselves. In those days, we’d have guests with divergent belief systems and opt for dinner party civility over possible discomfort among our guests.

These days, politics and religion are no longer taboo, for we tend to surround ourselves with those who think and vote and worship (or not) as we do. Ideological bubbles, some call them, and we live comfortably within their fixed confines. And I’m thinking these bubbles are sadly getting smaller as we become more and more disconnected from anyone who disagrees with us.